Since the 1950s, venture capitalists mastered funding the difficult—hard technologies—well before profits crystallize. Venture capital has long served as a bridge, spanning the chasm between a startup’s early vision and its market reality. Pioneers like Draper, Gaither and Anderson, and Davis & Rock paved the ground for stalwarts like Mayfield Fund, Sequoia Capital and Sutter Hill Ventures, nurturing the founders of firms like Atari, Apple, Cisco and Oracle.

This model has delivered extraordinary returns, refining a formula that balances risk and reward. It funds the creation of assets like a new algorithm or a hardware prototype, fuels the search for product-market fit, and, in later stages, pours resources into marketing and distribution to ignite growth.

For the last couple of decades, returns have come from building on internet platforms: the internet, then social, cloud and mobile.

Silicon Valley venture capital loves a new platform, and AI is that new platform. The latest data shows over half of all VC dollars flowing into AI. But could AI’s ability to vastly empower company builders challenge the VC model?

Venture capital is flooding into AI companies at a scale never seen before. In the fourth quarter of last year, more than half of all venture capital went into AI firms. I expect the dial will move towards AI when the data for this quarter are in. The “AI frenzy [has led] US venture capital to biggest splurge in three years.”

Investors have gravitated to a few behemoths. Billions have been funnelled into the largest firms in the sector: OpenAI has raised $17.9 billion; Anthropic $14.3 billion, x.AI $12.1 billion, Scale $1.6 billion. Just six large deals in the past quarter account for 40% of all venture investment.

Simultaneously, a countercurrent emerges: small teams—sometimes just a couple of founders—leverage AI tools to build products, reach customers and generate revenue with astonishing speed. Coding assistants churn out software in hours, not months; marketing automation targets audiences with surgical precision.

Last year, startups graduating from the prestigious Y Combinator incubation programme achieved new revenue growth rate records: the average team tripled sales during the 12-week programme.

In the words of investor Terrence Rohan:

People used to climb Everest and they needed oxygen. Today, people climb it without oxygen. “I want to summit Everest and use as little oxygen (VC) as possible.”

What’s driving this is AI. Small teams can do much more with fewer people. Product managers can skip the specification step and jump straight to working products, focusing engineers on the hard problems that AI tools might struggle to address.

If their products use large language models, those products are likely more useful than not. One team I know uses LLMs to improve administrative tasks. They doubled sales to roughly $2 million ARR in the most recent 12-week period.

Spending $40/month on a coding assistant to defray a junior hire pays back in hours. Founders on a dramatic revenue trajectory may need less capital to reach profitability—and very little capital after that.

So, we have a paradoxical duality. AI is a magnet for capital: those huge foundation models and infrastructure companies need cash for breakfast, lunch and dinner. But AI is also a solvent, dissolving the need for that capital.

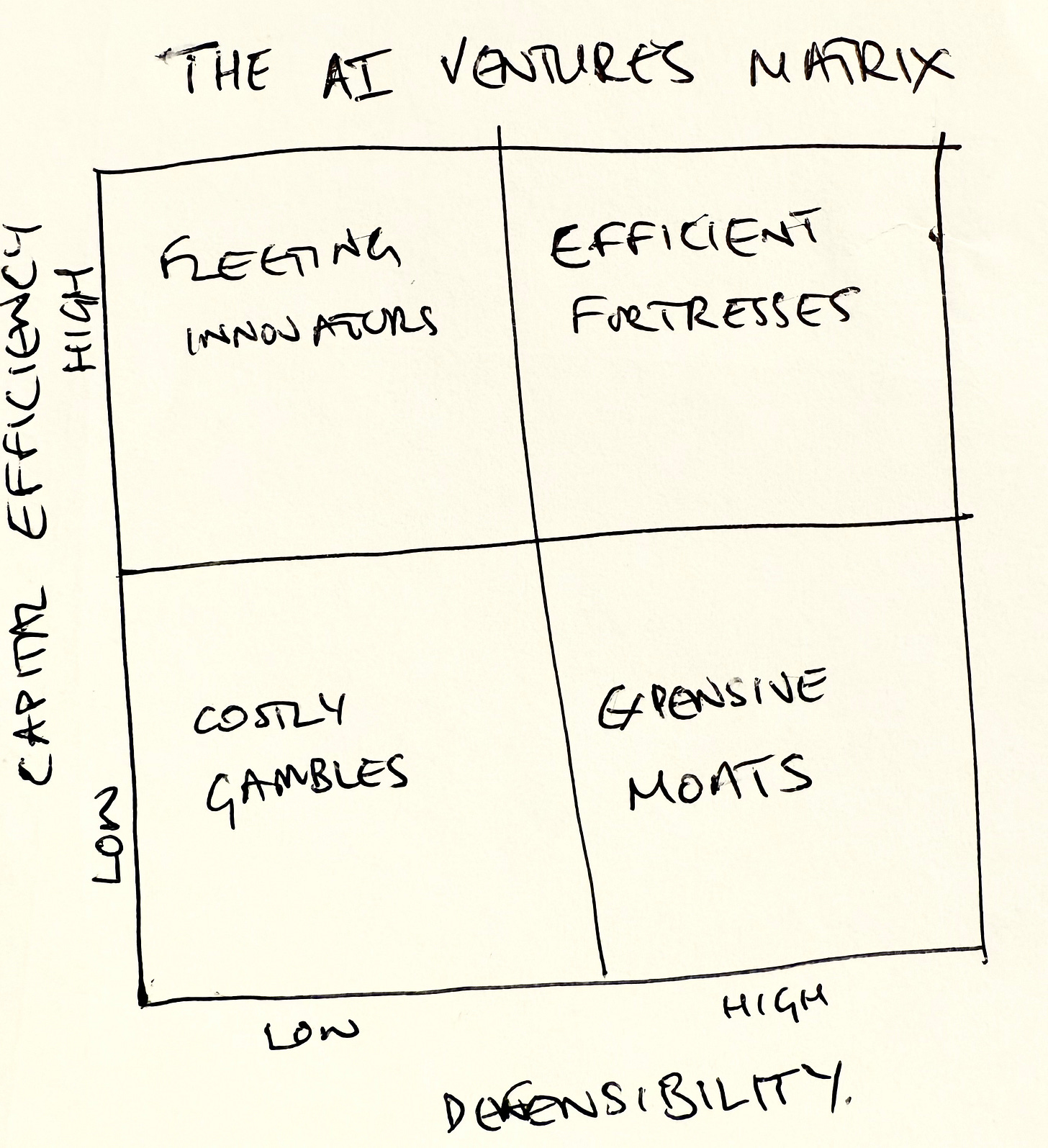

I thought about this across two axes: One, capital efficiency—how little money a startup needs to scale; and two, defensibility—how well it can protect its edge from competitors. These levers frame four distinct scenarios, each reshaping the funding calculus.

1. Efficient fortresses: High efficiency, high defensibility

Here, startups scale rapidly with minimal capital and erect formidable barriers—proprietary data, network effects, or brand loyalty. Think Alphabet or Microsoft, whose ecosystems and data troves create lock-in, sustained with relatively low ongoing investment.

These are the golden geese of any era: lean, resilient and enduring.

Google only needed $26 million to get to IPO. And only two venture capital firms, Kleiner Perkins and Sequoia, participated in any significant measure. If AI allows founders to grow defensible, capital-efficient businesses, will they seek out external capital with the dilution and loss of control it engenders?

2. Fleeting innovators: High efficiency, low defensibility

In this quadrant, startups exploit AI’s low entry costs to launch quickly, only to face relentless imitation. Snap Inc. and Zoom scaled fast with little capital, but their innovations invite copycats, shrinking their window of dominance. Zoom’s share price, for example, has returned 3.7% per annum since its IPO five years ago.

For founders, this quadrant might remain appealing. The lack of defensibility means constant reinvention, but capital efficiency means profitability while it lasts. Startups in this quadrant look like successful proprietary trading firms whose strategies may only last weeks before a new pivot.

This is an ugly space for investors who just want to get on the cap table. A path to defensibility matters because every bout of reinvention is more product and market risk you are taking.

3. Capital-intensive moats: Low efficiency, high defensibility

Some startups demand vast sums but once built, they stand impregnable. Tesla’s billions in manufacturing and Nvidia’s R&D dominance illustrate this. AI can deepen these moats—think autonomous systems or chip design—making the upfront cost a worthy bet.

4. Costly gambles: Low efficiency, low defensibility

The least appealing scenario: startups that guzzle capital without securing an edge. In previous investment waves, sharing economy startups like Bird and Lime fell into this zone. In an AI-driven world, these are cautionary tales—capital sinks with little staying power.

Can the most significant AI companies that build the models ultimately build capital-intensive moats, or will they become costly gambles?

With the pace of improvements, frontier-class models become commodities in months, perhaps weeks. Prices drop hundreds of times in a matter of months. Those expensive GPUs have a shelf-life. The accountants may depreciate them over five years, but the infrastructure managers know that a couple of years of hard running will leave exhausted silicon needing replacement. All this adds up to greater demands on capital.

AI’s most profound effect may be its push toward the Fleeting Innovators quadrant of high efficiency and low defensability.