We used semi-structured interviews and reflexive thematic analysis to explore the experiences of nineteen individuals who use generative AI to work on their mental health and wellbeing. Participants told us that generative AI feels like an emotional sanctuary, offers insightful guidance, can be a joy to connect with and can connect people to others, and bears comparison with human therapy (positively and negatively). A range of positive impacts were reported, including improved mood, reduced anxiety, healing from trauma and loss, and improved relationships, that, for some, were considered life changing. Many participants reported high frequency of use and most reported high levels of satisfaction.

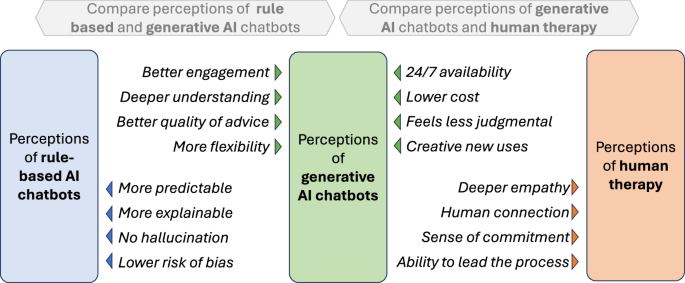

Our findings point to similarities and differences in how generative AI and rule-based chatbots are experienced. Many of the themes we developed are not new, but rather echo well-established user appreciation of rule-based chatbots’ always-available, non-judgmental listening ear and abilities to create a therapeutic alliance and reframe negative thoughts20,22. Other themes appear to be more novel, such as the level of joy experienced, the sense of being deeply understood, the breadth and quality of advice, and the ability to work on mental health in flexible and creative ways, such as through role-play, imagery and fiction. Figure 4 tentatively summarises how perceptions of generative AI chatbots, rule-based chatbots and human therapy may compare.

Arrows point to the intervention with the perceived advantage. The advantages of rule-based AI chatbots summarise the literature mentioned in the introduction, all other comparisons are perceptions taken from participant interviews. The comparisons are suggestive and should be interpreted with caution.

The potential and challenges of generative AI for mental health are starting to be explored. Current literature tends to advocate for a cautious approach, in which near-term clinical generative AI applications are limited to implementations of evidence-based therapies (such as CBT)52, with a clinician in the loop52, and models constrained to scripted responses as far as possible42. But our study suggests that people may already be receiving meaningful mental health support from consumer-focused generative AI chatbots, which are widely available, largely unconstrained, and function without clinician supervision. Therefore, a better understanding of the safety and effectiveness of these tools should be a priority.

On the topic of safety, our study offers observations in two areas. First, the inappropriate, harmful, risky or narcissistic behaviours observed in early generative AI chatbots53,54, which were influential in informing the literature advocating for caution42,52, were not mentioned by any of our participants. This should not be considered evidence of absence, but more research may be warranted to assess whether the risks have changed with recent technological improvements, or whether these issues are simply rarer, requiring larger sample sizes to uncover.

The second observation on safety relates to how generative AI chatbots respond to users in crisis. Given the unpredictable “black box” nature of generative AI43, and the existence of at least one tragic example of early generative AI chatbots supporting users in dying by suicide55, current literature advocates that when users display signs of crisis, models revert to scripted responses that signpost towards human support42,51. Guardrails like these are commonly implemented in consumer generative AI applications50. But this approach may be oversimplified in two ways: (1) by underestimating the capabilities of generative AI to respond to crises, and (2) by limiting those capabilities at the times that matter most. Several participants experienced meaningful crisis support from generative AI, as long as guardrails were not triggered. This resonates with recent research showing that generative AI can help halt suicidal ideation48, and that young people show a preference for generative AI support responses over those from peers, adult mentors and therapists – but not on topics that invoke the AI’s safety guardrails32. Moreover, the closest that participants came to reporting harmful experiences were those of being rejected by the guardrails during moments of vulnerability. Therefore, providing the safest response to those in crisis may require a more nuanced, balanced and sophisticated approach, based on a more complete understanding of capabilities and risks.

For researchers, we need to better understand the effectiveness of these new tools, by comparing the impacts of generative AI chatbot use on outcome measures such as symptom severity, impairment, clinical status and relapse rate52 against active controls, such as traditional DMHIs or human psychotherapy; and to understand for which populations and conditions is it most effective. These simple questions may not yield clear answers, as our study shows that generative AI chatbot usage is diverse, complex and personalised, and moreover, constantly evolving as the underlying technology improves. RCTs of generative AI implementations of standardised, evidence-based practices, e.g., CBT, could be one approach, at the cost of reducing the flexibility of the intervention. Another avenue could be large-scale longitudinal studies with sufficient power to account for the many variations of generative AI chatbot usage. While such studies are prohibitively expensive with human psychotherapy, the low cost of generative AI could make them viable, potentially enabling valuable new insights into mechanisms, mediators and moderators of the human response to therapy52.

Another promising research avenue could be to explore user perceptions of the nature, capabilities, and limitations of generative AI, and how these act as moderators of the potential benefits and risks. Does a deeper understanding of the technical realities of AI increase access to mental health benefits and protect against potential harms? Such research could inform the development of educational tools and guidelines for AI usage in mental health contexts.

For generative AI chatbot developers, this study identified several ways in which these tools could be more effective. First, better listening, including more hesitancy in offering advice, shorter responses and the ability to interrupt and be interrupted. Second, building the ability to lead the therapeutic process and proactively hold users accountable for change. A prerequisite for this is human-like memory, including the ability to build up a rich and complex model of the user over time. Third, richer, multimedia interfaces, for example by visualising the conversation as it unfolds, or with more immersion through virtual reality.

While only a few participants mentioned a need for greater accessibility, the well-educated, tech-savvy nature of our participant sample suggests that the benefits of this technology may not currently be connecting with the full population who need mental health support. One approach to address this could be to create solutions targeted at specific populations or conditions; another could be to find better ways to introduce users to the technology, for example, through the “digital navigator” roles proposed to connect users to DMHIs56,57. In any case, for these tools to remain available, there appears to be a need to develop sustainable business models. While some participants suggested they would be willing to pay for access to generative AI chatbots, research suggests most users would not58, and the path to health insurance funding is not easy59. To illustrate the challenge, Inflection, the company behind the Pi chatbot used by most of the participants in our study, pivoted in March 2024 from providing consumer emotional support services towards enterprise AI services, due to a lack of a business model, and despite USD 1.5 billion of investment60. Lessons learned from attempts to scale up DMHIs may offer insights here61,62,63,64,65.

Finally, for clinicians, our study found that for some participants, generative AI chatbots were a valuable tool to augment therapy. A recent survey showed clear reservations among therapists towards AI66. To avoid giving clients the impression that, as one participant put it, “my therapist is afraid of Pi,” we recommend clinicians build their awareness of the potential benefits and limitations of these tools, potentially by trying them out first hand, and consider discussing with patients if they are using them and motivations for such use.

Our study has some limitations. While our convenience sampling strategy resulted in a diverse set of participants by country, age and gender, many populations and groups were not represented. Most of our participants lived in high-income countries, were tech-savvy and well-educated, and focused on milder forms of mental health conditions; and all had self-selected to participate, potentially introducing bias towards positive experiences. This study may miss important experiences from individuals where the mental health treatment gap is most urgent, and from individuals for whom the technology did not work.

As with all reflexive thematic analysis, there is a degree of subjectivity in how themes are developed, especially when conducted by a sole researcher (SS). However, this also affords a level of immersion in the data across themes and participants that can promote consistency and depth of analysis, with AC’s reviews of codes and themes helping to ensure rigour and validity.

In conclusion, generative AI chatbots show potential to provide meaningful mental health support, with participants reporting high engagement, positive impacts, and novel experiences in comparison with existing DMHIs. Further research is needed to explore their effectiveness and to find a more nuanced approach to safety, while developers should focus on improving guardrails, listening skills, memory, and therapeutic guidance. If these challenges can be addressed, generative AI chatbots could become a scalable part of the solution to the mental health treatment gap.