When Jason Kelly’s 95-year-old grandmother died, he decided instead of reading her obituary, he’d listen to it. So he generated a podcast conversation between two virtual hosts using an artificial intelligence tool.

“It really, truly brought her to life as if she was sitting with me in the car,” Kelly said. “I actually learned a couple of things about her that I didn’t know.”

That’s just one of the ways AI is changing how people consume information, and as a result, shifting the playing field for journalism.

For some news people, AI is a death knell. AI-generated slop now blankets social media, crowding out work from real people. Meanwhile, AI tools openly steal from news sites.

But for many, AI is an opportunity, and perhaps even a lifeline. Easily turning written work into audio — which some news organizations are already doing — is just the tip of the AI iceberg, especially for small outlets with few resources.

That’s what brought Kelly, a software engineer with no journalism background, to the University of Minnesota in late January for an AI hackathon put on by the Minnesota Journalism Center, Hacks/Hackers and the U’s Data Science Initiative.

Roughly 50 people across 11 projects rushed to prototype AI-based journalism tools in just two days. The winning prize: $10,000 to support further development.

The mix of participants, spanning all ages, included local journalists, computer science students and interested community members.

The focus of the hackathon was “making local civic information more accessible.” That resonated with Kelly, who was born and raised in Fosston in northwestern Minnesota, which is served — poorly, Kelly thinks — by The Thirteen Towns newspaper.

“There’s really not a lot of investment, in terms of journalism, and people that actually cover…the community,” he said.

Kelly wanted the paper to have the same sense of dynamism he felt AI gave to his grandmother’s obituary. So he worked with a group of six others on an AI newsroom concept.

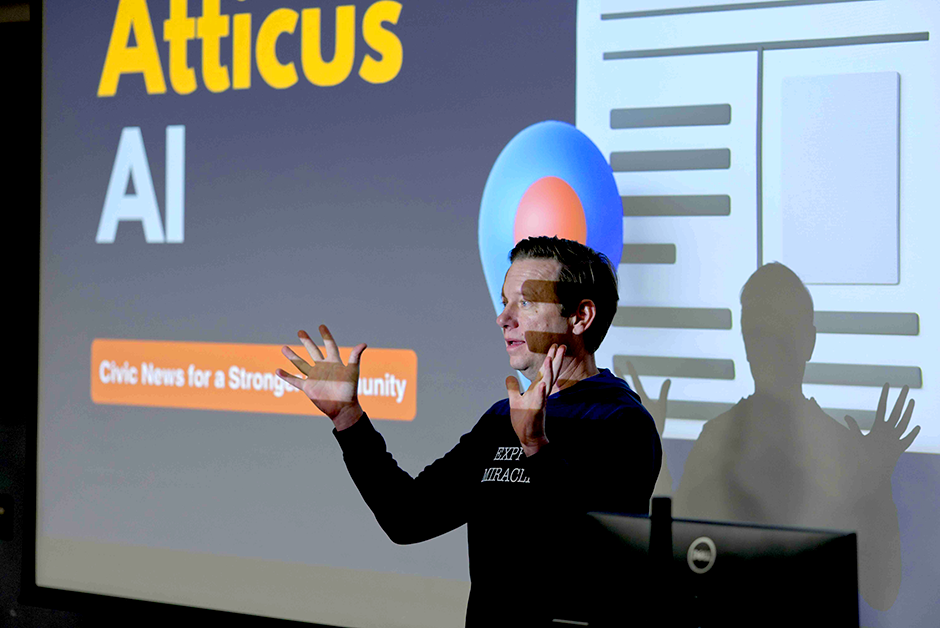

Called “Atticus AI,” after a journalism student in the group, the tool would theoretically aggregate local information, create written and audio summaries, and deliver it to residents with human approval. Then journalists could spend more time on human interest stories — the kind of reporting AI can’t do.

At some point, the journalism student felt awkward about how much AI would theoretically be doing. “You’re not cheating,” said Louann Berglund, a publisher from Fosston and part of the “Atticus AI” group.

“You’re actually, finally able to keep up with how fast [the news] is moving.”

A new frontier

The hackathon came from connections that Benjamin Toff, the director of the Minnesota Journalism Center, made while presenting research about AI and audience trust across the country.

He got to know Hacks/Hackers, a nonprofit bringing together journalists and technologists, which regularly puts on hackathons.

“We have been working on relaunching the Journalism Center, and trying to build connections across the practitioner community,” said Toff, who also serves on MinnPost’s board.

A hackathon “seemed like a really great opportunity to convene all these people and work on building some concrete tools that may be of use within the field right now.”

The hackathon was split in two parts: Two sessions at the annual Minnesota Newspaper Association convention, and then the actual event at the Hubbard School of Journalism and Mass Communication.

At the MNA convention, Hacks/Hackers led a brainstorming workshop with journalists from across the state about how AI tools could streamline their work.

Ideas ranged from using AI to track legislation about local issues to aggregating high school sports scores. Journalists recorded short videos pitching each idea, which were passed on to the hackathon.

Toff also presented on a panel about audience trust and AI, together with Alex Mahadevan, director of media literacy at The Poynter Institute, and Lynn Walsh, assistant director of Trusting News.

Some of the takeaways: Audiences trust journalists less when they use AI, while disclosing that use increases trust. But how best to show those disclosures, and figure out people’s tolerance for AI, is really about communicating with audiences through surveys, focus groups and organizational policies.

That was particularly interesting to Trevor Slette, publisher of the Cottonwood County Citizen, a southwestern Minnesota newspaper based in Windom. Slette has been working with a software engineer to develop AI tools for the paper.

The panel “spurred a lot of conversation on our end, especially if we’re going to delve deep into [AI] here,” Slette said. “I think it’s a wise decision to have these focus groups…just to pick people’s brains and see what they think about it.”

Slette is excited about how AI can help rural print papers, which he thinks are often overlooked by many, including in the journalism industry.

Print has been eroded by hedge funds and a too-little-too-late response to the primacy of the internet. But it can still be a successful medium for news — especially with a little extra help to free up journalists for more engaging reporting.

“If I could grab a little slice of that [AI] positivity that’s going on, I just think the market is huge,” Slette said. Unlike other digital changes, journalists are “at the forefront. We can be the leaders in this — although nobody really knows what that means right now.”

One idea Slette had, which he pitched during the MNA brainstorm, was an AI translation service that would help him reach a diversifying rural Minnesota.

Hackathon winners and caution ahead

Hackathon participants riffed on some of the ideas from the MNA journalists and also worked on their own concepts.

One group focused on an AI bot to gather and summarize information from local governments, which would help rural publishers with few staff trying to cover a large geographic area.

That kind of tool is a dream for Chelsey Perkins, the news director at KAXE northern community radio, who worked on the team. But trying to prototype it at the hackathon was a wake-up call.

AI has a lot of potential, but it’s not an easy cure-all to journalism ills.

“What I realized is just how challenging it would be to build something as large in scope [as] we envisioned,” Perkins said — and likely beyond KAXE’s capability and funding alone.

In the end, the hackathon winner was a group of three international graduate students from India studying computer science at the U. But their concept came with some controversy.

Erina Karati, Dipan Bag and Arunachalam Manikandan took Slette’s idea and ran with it to prototype an app called “MinneDigest.” Using AI, “MinneDigest” takes written news stories and generates text and audio summaries that can be translated to different languages.

“I don’t think that most minority communities within Minnesota…have access to such apps which can give you news content in 30-second summarized clips,” Bag said. “That makes it much more accessible.”

Source links feature prominently to build trust and let people read a full story if interested. Users would also have the option of turning a story into a two minute AI-generated podcast conversation with virtual hosts.

To prototype the app, the group scraped text from sites like MinnPost and Minnesota Public Radio News (already raising eyebrows) and plugged stories into ChatGPT for the summaries and translations.

But during the group’s presentation, it was the AI podcast that stunned some journalists, and exposed the deep anxieties news people have about AI.

“The podcast part was something we spent a long time figuring out,” Manikandan said. The group wrote a large ChatGPT prompt to tell the AI podcast hosts to “understand all the news that’s happening, mention the emotion that’s happening, because you can’t be excited for sad news.”

Crucially, they also prompted ChatGPT to name the hosts. One became Sarah, an inquisitive type. The other was Mike, intended to be more enthusiastic.

When Sarah and Mike started summarizing an MPR News story in relatively natural but still somewhat stilted AI voices, the presentation hall became tense. This AI tool was encroaching on real journalistic territory — after all, MPR News is already an audio-focused outlet with human hosts.

A former radio news editor audibly groaned and put his face in his hands. Other journalists looked around wide-eyed (including this reporter, who also started nervously laughing). Afterward, an MPR News producer took issue with the AI host names, as the organization employs real people named Sarah and Mike.

“It really was an encapsulation of some of the most alarming things…about what these tools can do,” said the MJC’s Toff, who was one of the hackathon judges.

But the podcast was also a clear sign that there’s no way for journalists to avoid the changes AI is bringing.

“These tools are going to be built one way or another, whether it’s by this team or somebody else,” Toff said. “My hope is that, by creating a space for connecting [journalists and software developers], it can maybe be built in a much more responsible way.”

That’s why the “MinneDigest” team has distinct guidelines as it continues developing the app over the next three months, supported by the $10,000 prize.

First of all, they need to partner with existing news organizations, so they can access stories without scraping sites. Then, during development, “MinneDigest” has to be built ethically.

That’s a commitment the group takes seriously. “We will be transparent on how it works, so that even when partnering with journalists, or when [someone] is using our product, they can be rest assured that we’re not crossing anyone’s boundaries,” Karati said. “We have not stolen anyone’s data or voice.”

The three students have many ideas about how to develop “MinneDigest,” and are excited to continue the project. There are a variety of challenges to overcome, including the need to speed up audio generation (impatient users won’t wait two minutes for a podcast digest to load) by creating their own code, and accounting for how inaccurate AI can be when summarizing news.

Regardless of who won or lost, the larger takeaway from the hackathon may be the inevitability of AI and the need for journalists to engage with it. But as journalists and non-journalists alike get excited about its potential, there is also serious risk.

“The only thing that a journalistic outlet has is trust, and if you screw that up, you’re done,” said Michael Olson, deputy managing editor for digital at MPR News, who participated in the hackathon.

“There’s a lot of what we saw in the demos today that we would never want to touch,” he said. “But it’s great — people are bringing different solutions to how they’re approaching the news.”