On January 20, the first day of his second term in office, US President Donald Trump signed an executive order—one of around a dozen—that rescinded a 2023 executive order signed by his predecessor Joe Biden on Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Biden wanted AI developers to align with the Defense Production Act because he believed AI poses an unprecedented risk to national security, consumers and workers. Trump decided that these guardrails were unnecessary.

The next day, soon after the Diet Coke button was reinstalled in the Oval Office, Trump announced that OpenAI, Oracle and SoftBank have together pledged a $500 billion investment over the next five years to create AI infrastructure—including data centres—under a joint venture called Stargate. He claimed that this investment would “almost immediately” create 1,00,000 jobs. The first data centre is reportedly under construction in Texas.

AI, the next arms race

Predictably, the leaders of these companies who shared the podium with Trump gave him full credit for this development. Meanwhile, the billionaire businessman Elon Musk, conspicuously absent, attacked the announcement and the leaders, much like the sulking teenager who wasn’t invited to the party.

It’s already clear that tech leaders cosying up to the mercurial Trump is a strategy destined to work. Under Trump, the US is likely to develop AI with a nationalistic, almost militant, zeal, and the focus may no longer be on how AI can be misused. Instead, the tech leaders will be allowed to obsess over how it can be leveraged to consolidate American hegemony. Alarming as this turn of events may be for billions around the world, it takes cognisance of the possibility that AI is the next arms race.

Also Read | Here’s why we need inclusive AI: a view from the African continent

On cue and without warning, China entered the stage. The world was introduced to DeepSeek R1, a new model from the eponymously named Chinese startup based in Hangzhou. News of its superior performance over ChatGPT spread like wildfire. Within no time, it became the most downloaded free app on App Store. Feeding the frenzy were claims—proven and otherwise—that the app was trained at a cost of a mere $6 million and that the data required to run it was much less.

Adding to the legend was the possibility that DeepSeek managed its feat with microchips having lower computational power because the US government had made top-shelf AI-centric microchips, such as those manufactured by Nvidia, inaccessible. But loopholes and back-channels have kept these chips flowing into China and it is at least theoretically possible that DeepSeek uses them, although reports indicate otherwise.

By January 27, DeepSeek had become popular enough to experience a cyber-attack and outages.

A shocking realisation

AI magnates in the US have long claimed that the study of AI will benefit hardware manufacturers, software developers, and infrastructure creators alike because of its unrivalled demand and insatiable hunger for computational power, complex algorithms, and server space. In parallel, AI was also considered an arduous and less-understood science. If AI was a mountain, it was deemed scalable only by mountaineers who have trained for years using the most sophisticated equipment.

Then along comes DeepSeek, scaling the same mountain with bare feet while wearing a pair of Bermudas. So shocking was this realisation that stock markets pummelled all American AI software and hardware players, wiping around a trillion dollars off their previous value within a few days.

Also Read | Who is afraid of DeepSeek?

It was inevitable that China would compete well in the AI race. The country was bound to find a way to circumvent restrictions that were far less stringent than those imposed by 20th century superpowers on “rogue nations” to prevent them from accessing enriched radioactive substances and nuclear technologies. But the speed with which a Chinese upstart company leveraged open-source AI code to beat US bigwigs at their own game has left the world breathless.

The development further levels the playing field in the imminent trade war between the US and China. Trump no longer holds the ace of AI-related sanctions to brandish as a bargaining chip during negotiations.

Does India have a vision?

Such advantages become crucial at a time when nationalism is on the rise globally, making countries even more self-serving and willing to ignore borderless existential crises such as climate change, future pandemics and, well, AI.

Which begs the question: Does India have the vision and will to matter in the world of AI? China has opened the door to AI innovation and proved to the haughty czars of Silicon Valley that smart ideas and fleet-footedness matter a lot more than gargantuan investments. Does India have the smarts to walk through this door?

In most innovative nations, technological advancements are powered by both the public and private sectors, with the two sectors often working in unison.

How about India? A quick search of the Indian government’s Public-Private Partnership website offers zero results when one searches ‘AI’. On January 27, Nasscom made recommendations to the Indian government for this year’s budget, and it included a call to create a “deep tech fund” to foster innovation. It remains to be seen if the government agrees.

Meanwhile, the Indian government’s own dedicated AI website makes all the right noises but has little to show as outcomes. In fact, it resembles an aggregator portal that lists startups, articles, case studies, and news on the field. If the Indian government is enroute to repeating the PARAM moment, there are no signs of it.

For those tuning in late, in 1985, India requested the US for its Cray supercomputer, and the latter denied the request citing the possible use of supercomputers in defence and other strategic areas. In response, India founded C-DAC (Centre for Development of Advanced Computing) and its first mission was the creation of PARAM, India’s first indigenous supercomputer.

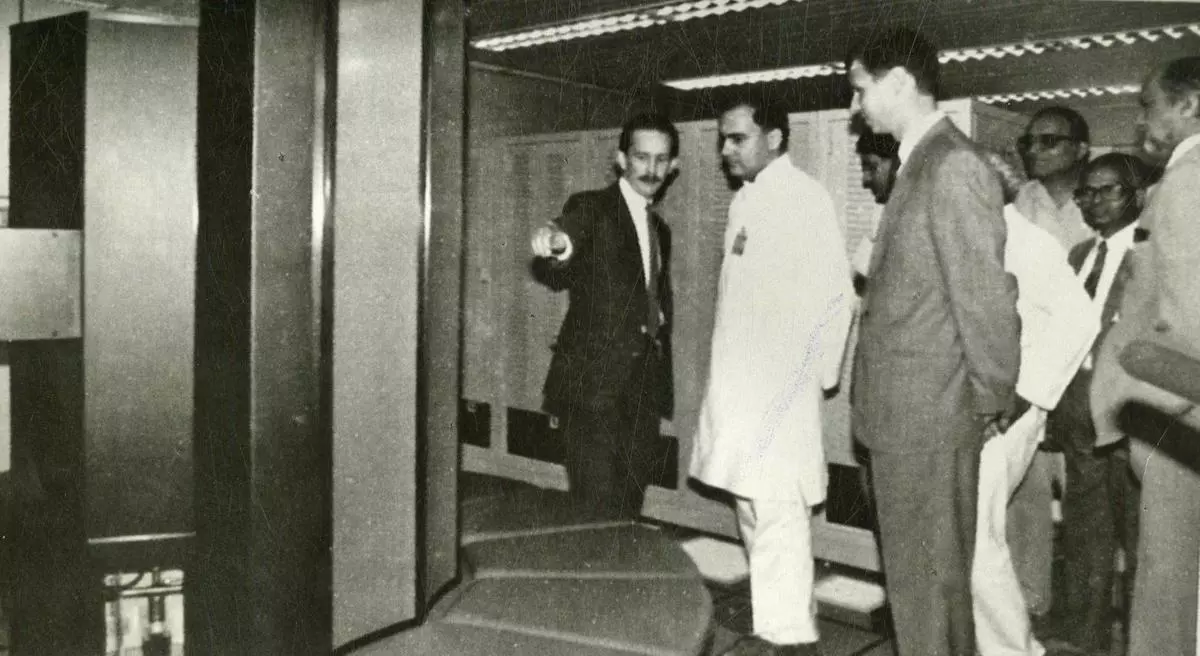

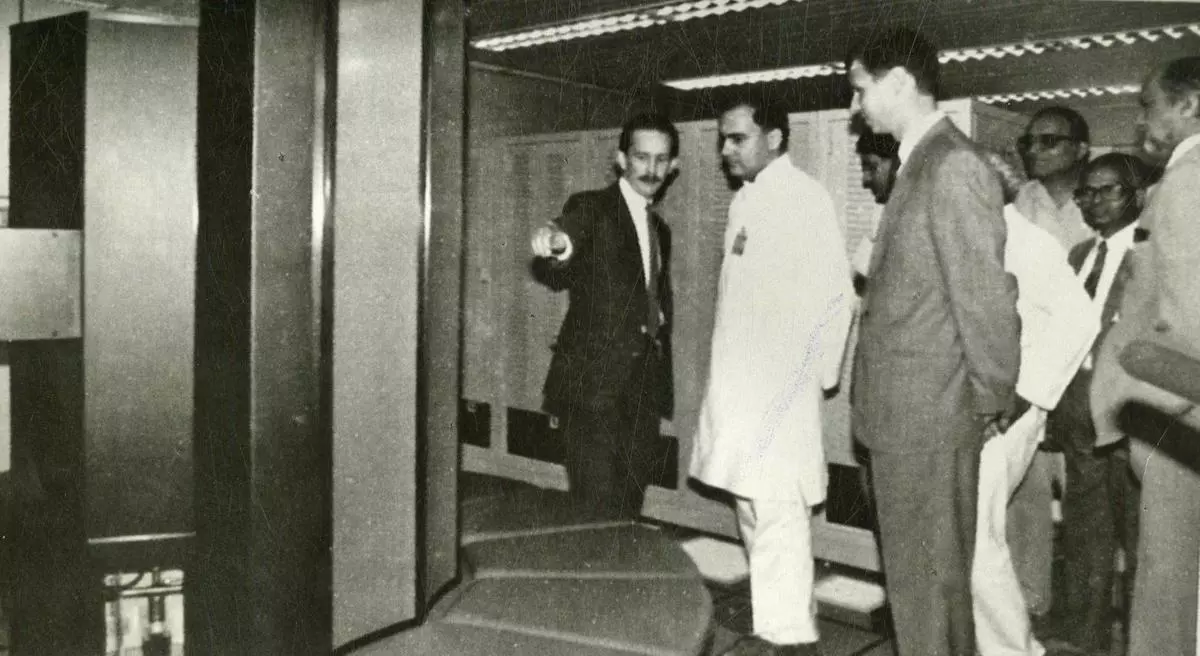

Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi dedicating the supercomputer to the nation, in New Delhi on March 25, 1989.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

It is a telling bit of history. It highlights how an impoverished and less educated nation can reach a seemingly impossible technological milestone using smart skills and determination. Surely, the nation could do better now?

At least on paper, there appears to be an intent to do more. The 2024 Budget allocated ₹1trillion for innovation under the Anusandhan National Research Fund, but this website again does not showcase any success stories so far. If such stories did exist, wouldn’t India’s mostly pliable media have announced them to us ad nauseum?

And what about the IT private sector, which has been feted for its glorious achievements as the world’s de facto software service-provider, and whose industry leaders have now become thought gurus for the nation? The fact is that not much has been said about the IT private sector’s failure to innovate and lead the world in the field.

In hindsight, it becomes clear that the greatest compliment one can pay the industry is that it leveraged a favourable exchange rate to convert person hours into revenue. And it managed to scale this idea from a few thousand IT workers to millions of them. Kudos. But the industry is like that child who aced high school but never pursued higher education. Rare IT innovations that happened in Indian companies have usually been undertaken by overseas entities that saw Indian talent in action in Silicon Valley and decided to set base in the home of that talent.

Former Infosys chairman Narayana Murthy’s recent statement that Indian youth must put in 70-hour weeks in order to build the nation highlights not only his blatant disregard for a balanced life and sound mental health, but also the servile manner in which the Indian IT industry earned its stripes. Why do better when you can do more of the same? Why lead when you can serve?

The truth is that innovation is a risky endeavour. It is fuelled not by large corpuses (that giant Indian IT companies have) but by brave hearts and grand visions. An industry that is obsessed with pinching paise and delivering satisfactory quarterly results can, by design, be neither brave nor grand. This aversion to risk is reflected in the fact that few Indian apps, software products, or websites have even a marginally global reach. The handful of operating systems and coding languages created in India have made an even smaller impact.

Tech for the grassroots

The argument that the best Indian brains get drained into the Western world does not hold water because it assumes that innovative minds come only from elite educational institutions that are funnels for this brain drain.

In fact, incremental improvements to India using AI seem to have come from unlikely sources. The Better India website reports how AI has been used to, for example, address human-animal conflict, fix potholes, keep soldiers warm, deliver healthcare in rural areas, and protect soil from chemical harm. These feel-good stories are important if for nothing else but to reiterate the difference that cutting-edge technology can make at the grassroots. That’s all the more reason for India to orchestrate its Big Bang AI moment.

In the long run, a messy American government dancing to the tunes of gluttonous American billionaires might be preferable to an uber-efficient Chinese government fuelled by unwavering ambition. But with the American empire collapsing in front of our eyes, China may well win this war. If and when that happens, the prosperity, maybe even the survival, of the Indian nation will depend on the scraps of technological prowess we accumulate along the way.

Unless, of course, we as a species decide to become silly and implement borderless solutions for borderless problems.

Eshwar Sundaresan is an author, freelance journalist, counsellor, life skills trainer, and bestselling ghostwriter.